Dear reader,

As befits the beginning of winter, the rain outside my window falls steadily from the heavens. I am glad: I love to see the grass turn the vibrant green that comes from plentiful rains, and my winter plantings—lettuce, rocket, and spinach, broccoli, brussel sprouts, and peas— receive the water gratefully.

The soils of my lawn and garden are ready to receive such a gift, their loam loose. It’s not a condition to take for granted. I’ve watered several houseplants whose compacted, old soil resisted the gift of water, allowing this life-giving substance to run through the soil or pool on top without being absorbed. Without intervention, the plants continue to refuse water, despite my attempt to give more, despite their desperate need for it.

Land, too, can develop this resistance, hardening through years of drought, neglect, or depletion. When the rains come, heaven’s gift is resisted. Instead of receiving with joy, earth stands opposed to heaven, refusing to yield—and so refusing to live.

We are not so different, with our hard hearts, from the hard earth. We naturally resist the grace heaven sends. The soil of our hearts needs attentive care—the softening which is the work of the Spirit, the replenishing which is the work of the Word. Without this care, we cannot receive God’s grace, and we cannot produce its good fruit. Our lives, like hardened, hydrophobic earth, will stand in opposition to heaven’s grace.

I wonder about my own heart, in particular, after a long year and a half now of pandemic conditions, of grief and unfulfilled longings. I wonder if it may be easier to harden, to grow tough from the political and cultural divides and the powerlessness that I feel— all pressing insistently into my daily thoughts.

I’ve written before in these letters about giving permission to mourn in a culture that loves to rush to the joyful conclusion. And yet perhaps, just as we can get stuck in a parade of victory, not allowing ourselves to sit in grief, we can also get stuck in sorrow. We can resist relief by seeing it as a betrayal or denial of suffering.

I was reminded of this as I re-read Sense and Sensibility last week. Marianne, the passionate middle sister in the Dashwood family, careens through the novel with intense emotions, first untempered infatuation with Willoughby, and then an equally indulgent sorrow when Willoughby scorns her affection. The point that Austen makes is not, I think, that passion is bad and all emotions must be carefully regulated. Marianne’s older sister Elinor attempts this, and while Elinor congratulates herself on her emotional control, Austen does not present her as a perfect model. Instead, I think Marianne’s immaturity was (she grows!) her getting “stuck,” if you will—holding on to her bliss or anguish at all costs.

One day, only one posture will be fitting, and all else banished; one day, joy will fill our hearts without end. But until then, our God both rejoices (Luke 15:7) and weeps (Jeremiah 48:29-39), and we ought to imitate him, seeking joy in what brings him joy, and weeping over what displeases him.

Our hearts need to be soft, ready to receive both sun and rain when they are given.

I wonder where you would say you land, more often than not, or perhaps in this particular season. Is joy or sorrow easier for you? Which do you resist?

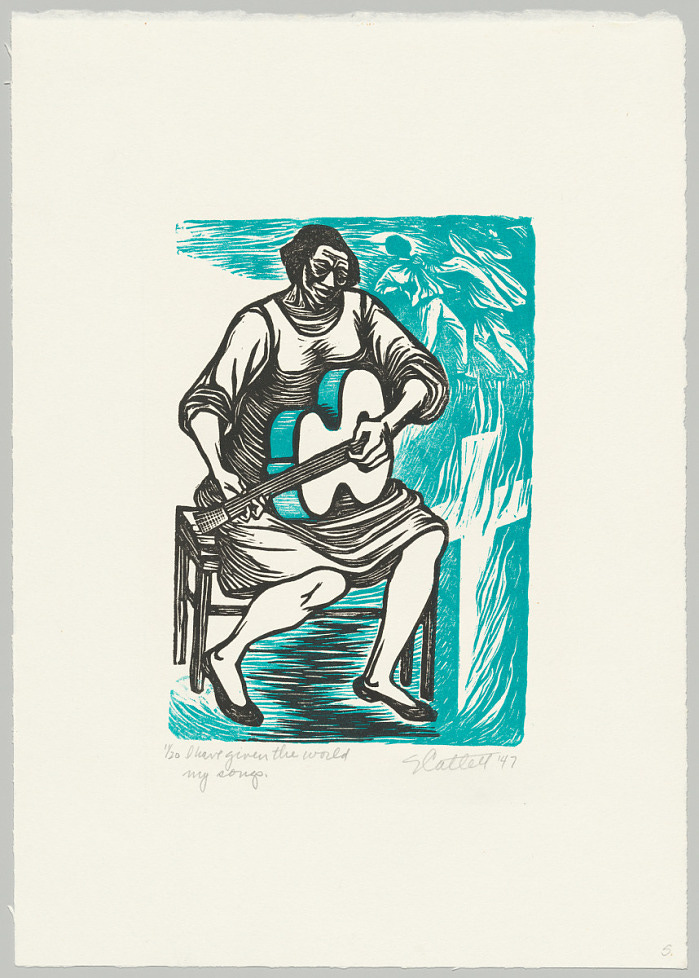

If we need an example of the ability to hold both grief and joy, one place to turn is our African American brothers and sisters. In their collective experience of enslavement and racism they have borne an incredible amount of suffering. Elizabeth Catlett, the artist of this linocut, “I Have Given the World My Songs,” had her scholarship to the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh rescinded because she was Black. In this piece, she portrays the anguish of her people. And yet, the anguish is not the dominant image—instead, the focus of the piece is the creativity and resilience of black women, to continue to give and to sing in resistance to the darkness.

From “Chronological Snob No More”: We are no different from our forebears, at least not in any substantive way. Our manners and methods may have changed, but we are not wiser, more moral, more faithful, or less naive than those poor, illiterate parishioners swindled by Chaucer’s pardoner, or those violent Roundheads and Cavaliers willing to defend their doctrine with their swords, or those rationalizing traffickers of human flesh, or those mercenary ministers treating their assignments like mere government posts.

From “It’s OK To Let Your Mind Wander During Prayer”: Instead of seeing a wandering mind as a failure, then, we should see an opportunity to pray about the deep longings of our souls. We are tempted to do the opposite: to stop praying and start chastising ourselves over an inability to focus or a failure to pray the “right” way. In these moments, we pause our talking with God because we do not think these are the kinds of things God wants us to talk about. They are our problems. They represent our wandering minds and hearts toward idols, worries, and loves. When these thoughts arise, it helps to pray, “Father, look at this. Look at what my heart does in your presence. Lord, deep in my heart, I long for control to calm my fears and anxieties. Lord, help me trust you with these.”

I’ve just finished Daniel Nayeri’s Everything Sad is Untrue, and I need to tell you to get a copy and read it right now. I read his sister’s memoir a couple of years ago, and it’s fascinating to read a story from the same family, but from an entirely different perspective. His sister, Dina, wrote in the form of creative nonfiction, meshing her own journey as a refugee from Iran to Oklahoma with the stories of other refugees in camps and struggling to find asylum in Western countries. Her anger over the broken systems fills her book, and I finished reading it with increased compassion for the world’s refugees, both those in her story and the ones that I meet in my work teaching ESL. Daniel’s book, by contrast, is marketed as YA fiction. Positioning himself as a type of Scheherazade, Daniel tells his story, along with myths and fables from Persia, to his incredulous and often ignorant classmates. Witty and insightful, he is a skillful storyteller, and I’m looking forward to rereading it, perhaps to the boys when they are a few years older.

About a month ago I bought (too) many books at a secondhand book sale, and I’ve been working my way through some of them. A couple in the stack were by Henri Nouwen, who I always enjoy reading. I finished his short work Reaching Out, an exploration of the spiritual life as reaching out—to our innermost selves in solitude, to others in hospitality, and to God in prayer. Nouwen reminds me that our culture of hustle, competition, and productivity, is not the way of Jesus.

I am no longer my own, but thine.

Put me to what thou wilt, rank me with whom thou wilt.

Put me to doing, put me to suffering.

Let me be employed for thee or laid aside for thee,

exalted for thee or brought low for thee.

Let me be full, let me be empty.

Let me have all things, let me have nothing.

I freely and heartily yield all things to thy pleasure and disposal.

And now, O glorious and blessed God,

Father, Son and Holy Spirit,

thou art mine, and I am thine.

So be it.

And the covenant which I have made on earth, let it be ratified in heaven.

Amen.

-John Wesley

On the road with you,

Laura