Dear reader,

I don’t know about you, but my imagination has been shaped to picture the love of God pulling his people away from the world, away from the physical realm and the creatures and places that compose it. I can still hear my grandmother’s gospel music, played on cassette tapes in her car: “I’ll fly away, fly away, oh glory, I’ll fly away.”

While we shouldn’t minimise the temptation to tether our hearts to create things, treating them as ultimate, particularly when it comes to people, we probably err more often on the side of lovelessness than loving too much. And the Scriptures tell the story of God’s movement, again and again, towards the earth, towards his creation, in love. I love the way poets have articulated this, whether Gerard Manley Hopkins’ image of “the Holy Ghost over the bent/ World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings,” or Richard Wilbur’s poem title “Love calls us to the things of this world.”

Yet there’s a generality to the words “creation” and “world” that can cause us to ignore the particular. It can be easy to pronounce, and even to feel, an expansive love for the world—for men and women and children in general, for flora and fauna as a whole. But can it really be love until it embraces a particular person or creature—not a category or a conglomerate? Can it be love until we are confronted with the smells and weaknesses and irritations of another being and still choose to move towards her in love?

Zosima, the key spiritual elder in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, preaches a message of love for all of God’s creatures, human and non-human. This may risk abstraction—an ideal so large that the particular creatures are lost in the whole. But Zosima understands the necessity of particularity, exhorting his students to love “both the whole [of God’s creation] and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light. Love animals, love plants, love each thing…Love children especially.” Zosima recognizes “that a man’s face often prevents many people…from loving him.” Convinced of the ideal of loving the whole world, we may yet hesitate from the actual.

We hear “love everyone!” and our imaginations easily supply a picture of needy and yet sympathetic faces. Perhaps this is why Jesus does not choose such a totalizing pronoun as “everyone” and instead instructs us to “love your neighbour.” He expands the definition of neighbour, of course, in the Parable of the Good Samaritan. Even so, I have felt the danger of letting loving my actual neighbours—the ones who are unlike me in every way, or pick quarrels with me or encroach on my time or property—give way to a willingness to love in a more grand way. Heroic willingness can seem an adequate substitute for mundane action.

But, as Rowan Williams observes, “God asks not for heroes but for lovers.” The great call of God on each of us is not ubiquitously to perform acts of heroism—as much as we may feel pressured by our celebrity culture to do something worthy of fame. Instead, it is to love, first, God, and then, as a result, each creature that he has made. Jesus’ words about faithfulness in the little things convinces me that until we learn love for the creatures and places near us, the ones that perhaps naturally repel us, we won’t have what is required for any greater, more heroic, act. Learning to love is not a quick undertaking, but, as Zosima observes, “it is dearly bought, by long work over a long time.”

What things—what particular, perhaps mundane or difficult—are you being asked to love today?

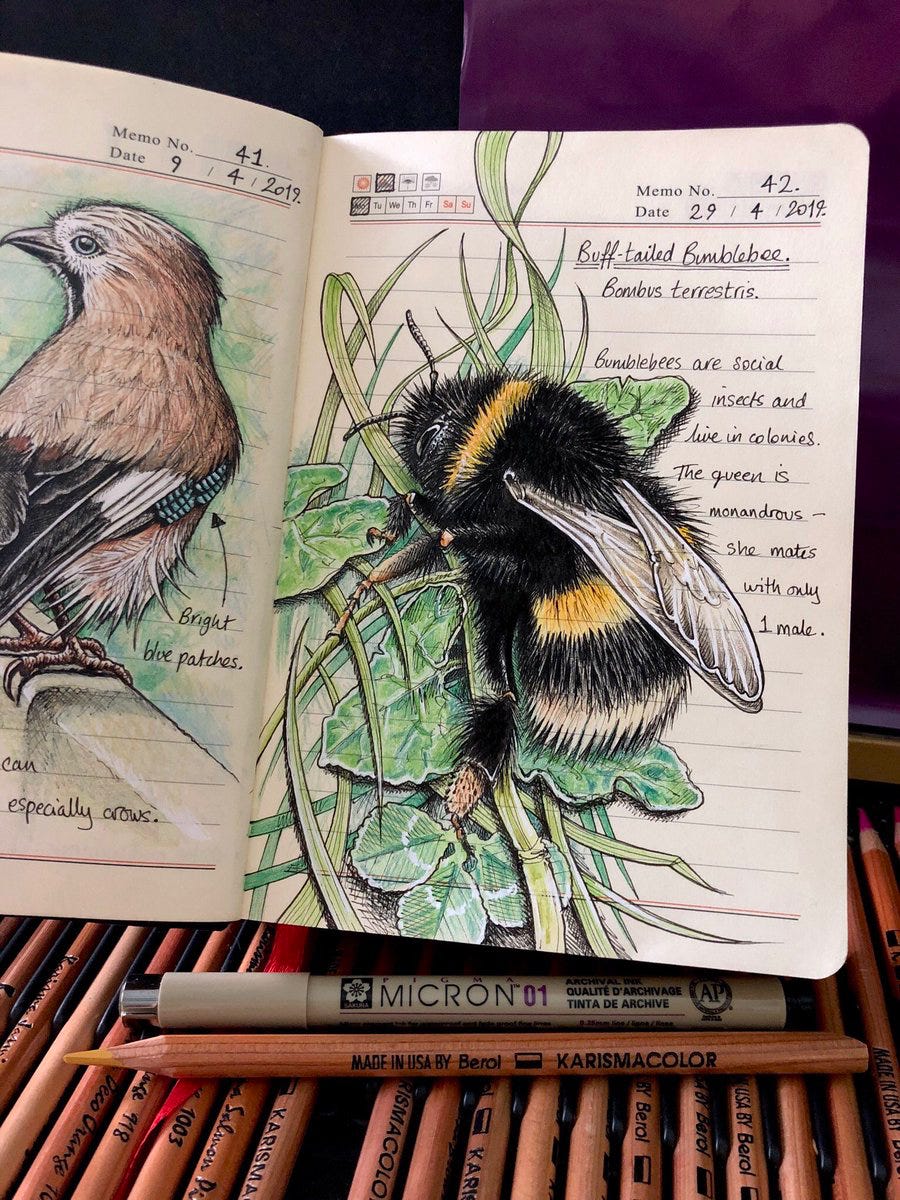

This beautiful page from illustrator Jo Brown’s published nature journal is the kind of thing I think of when I think about loving the particular. There is a special kind of love at work here, to notice what most people may pass by unaware. I wonder, too, if this kind of art that illustrates the natural world is not very important for our children, in a time when cartoon and caricature seems to be the most popular (or at least the most common?) way to represent creatures to children. It’s the kind of art that demonstrates love in its attentiveness to detail and absence of sentimentalisation.

It’s summer here—the school holidays are almost over!—and so my reading has mostly been of the quick, light novels of Alexander McCall Smith. I enjoyed catching up with the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series with the latest two instalments, and continuing to read the Scotland Street series as well. I love McCall Smith’s wit and insight into human nature. His sympathy and kindness cover each of his characters (well, maybe not Violet Sethopho!), and reading his stories prompts me to offer the same to those that I meet, especially those whose stories I know only a very small part of.

My evening read for the past few months has been Thomas Merton’s Seeds of Contemplation, which I went through very, very slowly. The problem with reading before bed, I’ve found, is that frequently my mind is too hazy to really digest what I’m reading. Which is to say that I’m not sure I can give an accurate, full summary of the book. Instead I have an impression: I was challenged by his insistence on internal integrity and humility, an attentiveness to the inner life that matters above all because without it we’ll fall to pieces. Hopefully

I’ll be able to come back to the book again someday—during my daytime reading!

My writing elsewhere this month: Desiring Significance at Velvet Ashes.

O Lord, you who send rain upon the righteous and the unrighteous, may we extend your kindness this day not only to family and friends, but also to stranger and enemy, so that we might be worthy to be called children of our Father in heaven. We pray this in the name of the One who purifies and perfects all human loves.

Amen.

On the road with you,

Laura